This story is inspired by Bernard Shakey's unsung

cinematic masterpiece, Human Highway,

and is dedicated to Samuel Delany's omniscient grin.

The Light in Apollo Diner

A dime of sunlight flits across her forehead. It dances first across her brow, then cheek, then neck. A solar baptism. Only when it alights on the curling edges of her notepad does she notice it. She looks up.

Across from her, dirt-dappled windows run the length of the diner. Through the windows, many miles away, above the mountains not yet lit by the rising sun, four silver ships, like metallic fingernails along a chalk board, screech into the early morning sky. They are high enough to catch the sun's low rays and throw them back to her, here, in the diner, which never closes.

She shuts her eyes. In a moment, the hanging pots will rattle as the ships' thunderous farewell rumbles through the valley in their wake. A little bell rings. The door swings open. A child sits down at the far end of the bar. The bell rings again, in comes another.

Why'd you sit there? Let's get a table.

I like the bar.

You like it because it makes you feel old, I bet.

Yeah. So?

You're never gonna get old.

So?

Do what you want. I'm gonna catch the takeoff. Hey -- lady!

The waitress points to a free table at the other end of the diner. The kids, both maybe fourteen, amble over to the empty booth, and with their sleeves, wipe the streaks from their window to see the white trails of the silver ships. Tanned elbows peek through holes in their rusty sleeves. Goggles dangle from their necks, lenses cloudy with red dirt. Neither of them wear shoes.

What'll it be, gentlemen? she says, pouring out two dusty cups of water. She untucks a chewed pencil from behind her ear and looks past them out the window. The ships disappear into the white sky among the raining silhouettes of falling birds. The mountaintop's turrets will shoot anything in range.

Coffee, and 3 eggs, please, says the kid who came in first.

How do you want 'em?

Sunnyside, please. Two regular, one good.

Good? says the waitress. You can't afford a good egg.

I can! the boy insists. I did some extra work at the yard -- look. He reaches into his pocket and three square coins, green with the green patina of age, fall heavily on the table. The other boy's eyes grow wide.

You weren't kidding! he says.

I told you, says the boy who wants the good egg.

The waitress looks at the three coins, then back at the boy. What kind of work did you do to get these? she says.

The boy casts his eyes down and does not reply.

And what about you? She turns to the other boy. Same as him?

Yeah, 3 eggs, sunnyside. But only regular eggs, please.

She looks back at the first boy, then the other, and shakes her head. A good egg for each of you, just don't go tell anybody.

She swipes a coin into her pocket and waits for the boy to take back the other two. His hands, seven long fingers each, are bruised and scarred from years of shipyard labor, but nimble from many more years of pickpocketing.

On her notepad, she writes: 2 good eggs, 1 regular, sunnyside. 2x. She tears it and puts it on the line, then rings a bell. The cook, smoking quietly in an unseen corner of the kitchen, emerges like a hermit crab to take the order, grunt once, and get to work. Sometimes he'll go weeks without uttering a word. The waitress doesn't mind; when the cook does talk he isn't very friendly. But it does get lonely here.

Here: seven booths, all empty but the one with the kids. Big windows, a broken clock, the walls a hazy green. Lamps without lightbulbs hang from the ceiling. It's so bright outside that the diner needs no lights. A droning fan drifts back and forth above the register, and does nothing. In the register: almost nothing.

Used to be that at a place like this, this early in the morning, there would be a line out the door. Crammed into booths and pressed against the big windows, visitors would come to see the ships launch from the mountaintop: departing in the morning, and -- with any luck -- returning just in time for the dinner rush.

And almost every hour, the guests would listen to the ships' reports, crackling from a radio turned up as high as it would go. Among quietly clanking silverware, the pilots would announce the news. Found a good sized rock, comparable gravity, but no water whatsoever. Not habitable. Or: Volcanic activity abundant, but too dense. Or: A hot one. Too hot. Couldn't stay here.

This was the dream: to strip what was left of their overheated, irradiated planet, and build newer, bigger, faster ships, to find another home. They had the means to do it, of that they were sure; all that remained was to find somewhere to go.

But one day, no reports came. No ships returned. The radios were silent.

At first, in the diner, disappointment. Then panic, not just in the diner, but everywhere among the seven hundred million human beings left alive, the children of the children of those who in the previous century had survived extinction by escaping to this thawed desert continent at the bottom of the world, to survive extinction. And probably that was the moment when, for everyone, the preposterous dream of escaping the mess left behind by their parents' parents began to die.

After four days of radio silence, a single ship appeared in the sky. It came in quickly, black clouds of smoke spiraling up as it spun down into the mountain -- and crashed. For ninety-three hours it burned. When it was done burning, nothing was left but a crater. And in the middle of the crater, sparkling as if brand new, a silver locket, shaped like a heart. Rumors of it spread quickly, almost as quickly as the noxious fumes that darkened the sky in the wake of the flames.

For weeks, no sunlight pierced the clouds. And even as the air outside poisoned a third of what was left of everybody, the heart-shaped locket changed hands. First, according to rumor, someone had it in a village seventy miles east. A mushroom cloud buried that town. Then, a year later, the waitress overheard a man who claimed he'd seen it on a strip-mining boat headed north. The boat, as far as the waitress knew, never returned. The man died shortly after.

Nobody down here in the valley knows what happened to the locket, but the waitress has seen a handful of counterfeits over the years. She was once even offered one by a drunken woman who asked for her hand in marriage; the waitress declined. For some, it became an idol of the hope of escaping into the stars. For others, and for the waitress, it was an obviously bad omen. But still she wondered...

These days, the ships that leave from the mountaintops do not return. Nobody in the valley knows where they go, either, and anyone who asks is decommissioned from the shipyards. So nobody asks. But every few months, another handful of ships disappear into the sky, tin cans cobbled together from salvaged metal. Only static on the radio.

The sun is all the way up now, brightly shining on the valley.

Above the dishwasher, glasses begin to rattle in their crates like anxious little windchimes. The waitress reaches up to quiet the pots and pans, and with her free hand steadies herself against the countertop. The cook turns down the flame on the stove and takes another drag from his cigarette as he waits for the rumbling to pass. A wave of red dust, kicked up from the blast, coats the windows. The waitress meets eyes with the boy who paid for two synthetic eggs and one from a living bird, for him and his friend. His lip trembles. He's not scared, but he's almost crying.

Then it's done. The cook rings his bell. A little wisp of smoke escapes from the kitchen window. Before he can crawl back into his cave, the waitress says: Wait.

He waits.

Do you know those kids? asks the waitress, lining up the plates along the length of her arm.

The cigarette bobs up and down on his lip. No.

The one on the left, says the waitress, he has seven fingers. He's from up north.

The cook grins. From the mushroom kingdom, eh?

That's not all, she says. He tried to pay with this.

The cook looks at the chipped token in her hand and grunts. So he works for someone mountainside. Maybe he killed someone. That's what you're thinking, right? What's it to you?

I don't know, she says. But if he's working for someone mountainside... but he can't be...

The cook slinks back off into his lair, leaving the waitress alone with her thoughts and her plates. For a minute she hardly moves. She allows herself to wonder: Up on the mountain, behind the turrets, where the ships come from... what happens?

I'll answer your questions, says the boy. She jumps, almost dropping the plates.

My friends want their breakfast, the boy continues. I came over to get it, and to tell you to meet me outside. I don't want them to hear anything.

She hands over the food, and the boy returns to his seat.

Three minutes later, they are huddled in the shade beside the chicken coop where, surrounded by barbed wire, some of the last chickens alive on Earth are not doing well.

I did get these coins mountainside, the boy says. I was paid to kill someone. He was not a good man. But he didn't suffer, I promise.

Squinting in the bright light, and almost as tall as her, his eyes meet hers. She does not know what to say. So he says: I won't live long. They'll kill me when they find me.

I won't tell anyone, the waitress says. The yards are a good place to hide. Anonymous. Goggles, masks. They won't find you.

They will, the boy says, I know they will. Because I have this.

He holds up his hand, a bright silver chain woven through his seven fingers. A silver heart hangs from it, catching and throwing the sunlight as it slowly rotates. The boy says: I took it from the man I killed. I'm a good killer, that's why they hired me, the folks on the mountain. I've killed people who were supposed to have the locket, only they were fakes. But this one's real.

The waitress is quiet. The locket does not rotate back and forth as it hangs, but spins counterclockwise, slowly, continuously, like a planet. She says, How do you know it's real?

If I show you, says the boy, I think you'd die.

Show me.

Three long fingers hold the locket steady -- one on each curve of the heart, one at the bottom point -- while another finger works the latch. It clicks. Two fingers, one on either side of the seam, ready to open it. With his last finger, the boy points not to the locket, but to her. He says, Look--

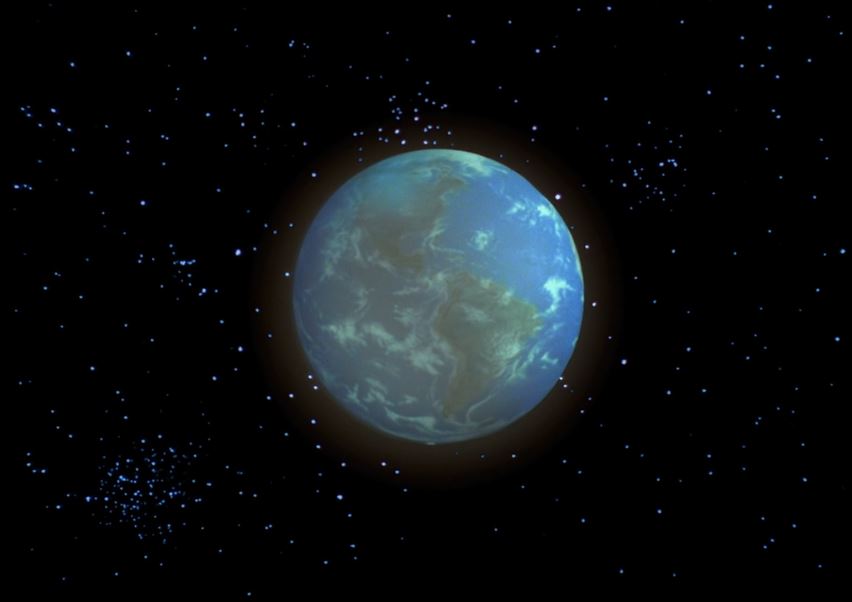

Then it's open. And the clouds turn to gold. And the mountains fade, and it's warm, not hot, and there's a sun, many suns, too many suns, all around her. They are bright but not blinding. How far away they are, or how big she is, she cannot tell. And she can hear them, the suns, whispering loudly, very close to her. They sound angry. What they're saying she can't tell. Like a sun, her heart is beating. Oh my god. Then a planet. Earth? Many planets. One green. Only one. The boy smiles. A solar baptism.

-

-